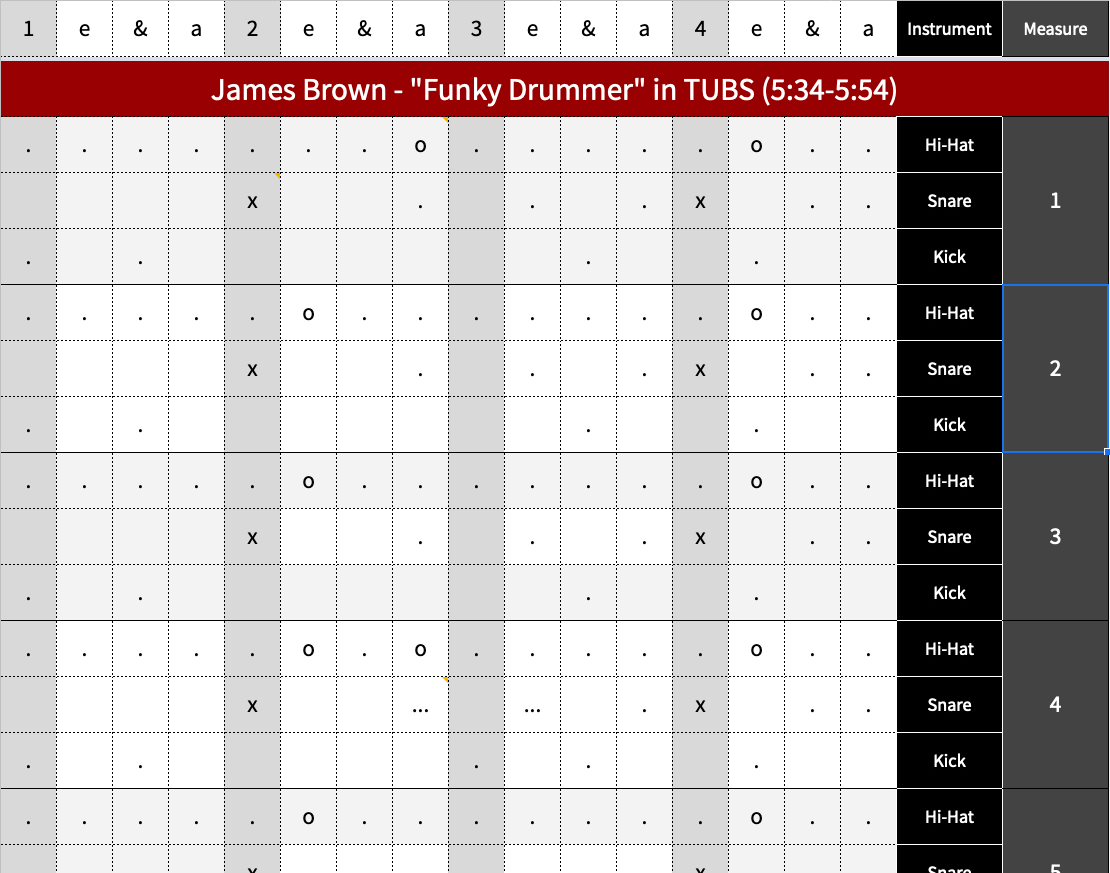

In TUBS, the boxes of a grid represent equal units of time, consistent from column to column, and from row to row. This is how MPCs, MIDI sequencers, and many DAW piano rolls work today. If there is an event in a Time Unit Box, play it. If there is no event in the Time Unit Box, don’t play anything. The process is repeated for the next box, and so on, and so on.

In Standard Notation, with respect to Rhythm, musical events are represented by a combination of note heads and stems, as well as their respective rests which convey explicit note durations and silences according to the composer’s idea of what the performer should play. The composer instructs not just when music happens, but how long it should be when it does, and how long it shouldn’t be when it doesn’t. The performer is expected to read and decode the symbols and excel at it if they wish to have full access.

But what happens if the reader does not excel at reading and decoding? What happens if the reader has no access to the composer’s transcription?

I sought out an alternative.

In the first example, I have transcribed something breakdancers know and love, James Brown’s “Funky Drummer,” in TUBS format.

This how I think about Rhythm. This is how I organize what I am hearing, Melody and Harmony included.

In the second example, I’ve transcribed an old bass line from my middle school days by Cake. This is a modification of TUBS, where notes are instead represented by Scale Degrees, placed in rhythmic context without obscuring their melodic function.

In the third example, I’ve transcribed a classic chord progression from Bill Withers, placing his broken chords in their rhythmic context without sacrificing their harmonic function.

TUBS is an intuitive, fast, communicable, and modular alternative. It gives Clyde Stubblefield’s snare buzz strokes, each of Gabe Nelson’s (I had to look his name up) bass notes, and every Bill Withers bass note and broken chord a location on the grid, a kind of rhythmic address. The result, taking from what James Koetting and Philip Harland saw back in 1962–1970* making it a theoretically instructive and listener-centric alternative for our modern purposes, is what I call the WARRENMUSIC Grid. It’s my attempt to bridge the gap between the rich history of the Western European tradition of music, and the new music of today.

This is how I learn new songs, and how I share what I learn in a digestible way with others.

If nothing else, TUBS is simple, and unassuming. I would argue that it is more universal. After all, music has gone digital.

Where I use Scale Degrees for Melody, you can easily use Note Names instead. Where I use Chord Numerals for Harmony, you can easily use Chord Names. Now it’s yours.

Check out the full transcriptions, along with note-for-note MIDI clips and video breakdowns of four other songs I’ve selected, transcription exercises, visual aids, and more in my upcoming Rhythm Module.

Scale Spelling Wheel — Exterior: All Note Names, Interior: Degrees of the Major Scale

Scale Spelling Wheel — Exterior: All Note Names, Interior: Degrees of the Major Scale